Mushroom Identification

By Chris Byrd

Mushroom identification can be a challenge. Many species look, smell and even taste similar. In addition, the look of a given species often changes over time as the individual mushroom ages. Despite the challenges, mushroom identification has become an increasingly important skill as more people have taken to the woods in search of edible and medicinal species.

As with plants, being able to identify mushrooms correctly is an extremely important skill if any amount of mushroom is to be used internally.

A relatively small portion of mushrooms are poisonous, and even fewer are dangerously so. However, even with the low percentage of dangerous species, a single mistake can have major health consequences underscoring the importance of proper identification.

With time, patience and hard-work anyone can learn to identify wild mushrooms accurately; opening up the world of mushrooms for culinary, medicinal, and ecological perusal and enjoyment.

What is a Mushroom?

The structure that we commonly refer to as a mushroom is in fact the reproductive structure of an organism that occurs primarily within the humus layer of the soil called the mycelium. The mycelium resembles thinly stretched cotton balls and is often found adhering to plant debris within the forest understory.

The sole reason the mycelium puts energy into the production of a mushroom is for reproduction. Every portion of the mushroom exists in order to disperse spores.

The cap functions as an attachment site for the gills which hold the spores on special structures called basidia (some mushrooms have other types of spore bearing structures). The cap edges raise over time to expose more of the gill surface to air currents.

The stipe (also known as the stalk) functions to hold the cap as well as to raise the gills above the dead zone of air that exists immediately at the ground's surface.

The mushroom itself is composed primarily of water, therefore mushroom production is limited to times where excess moisture is available. The spores themselves are adapted to be released during wet times by being hydrophobic.

Mushrooms fall into three primary life histories based upon how they procure nutrients: (1) Saprophytic, (2) mycorrhizal, and (3) parasitic.

1) Saprophytes - Mushrooms that have a saprophytic life history exude chemicals that break down plant and animal matter within the soil. These species are key decomposers within forest ecosystems.

2) Mycorrhizal - Species that are mycorrhizal form mutualistic bonds with the rootlets of plants. The fungal hyphae (small branching’s of the mycelial mat) intertwine with plant rootlets. The hyphae either enter the rootlet (endomycorrhizal) or wrap around the rootlet (ectomycorrhizal). The bond between the two results in increased water and soil nutrient uptake by the plant (and increased disease resistance) in exchange for a portion of the photosynthetic products of the plant (Carbohydrates) that are transported to the root system from the leaves through the phloem tissue of the plants cambium.

3) Parasitic - Parasitic species feed on the cambium tissue of living trees eventually killing the tree. The honey mushrooms, genus Armillaria, are perhaps the best known example of a parasite.

Mushroom Identification:

Identification of any species proceeds most efficiently from the macro perspective to the micro and mushrooms are no different. The first feature of a mushroom the observer needs to determine is the overall form of the fungus in question.

Major morphological groupings:

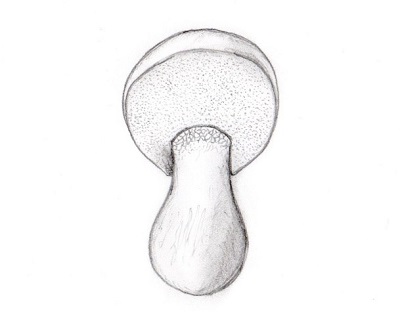

1) Gilled mushrooms: Mushrooms usually with a distinct stipe and cap. The spore bearing surface is composed of blade-like gills covered in spore producing structures called basidia. (Ex. Genera: Russula, Lactarius).

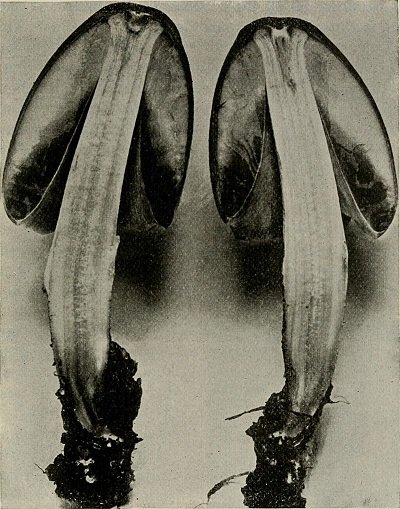

Example of a mushroom with blade-like gills

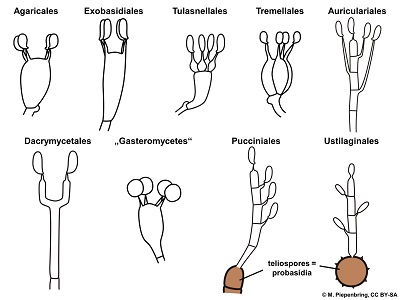

Example of a mushroom with blade-like gills Different types of basidia

Different types of basidia2) Mushrooms with rudimentary gills: Morphology similar to the standard gilled mushroom, however the gills are rounded instead of blade-like and often have smaller gills connecting the larger gills. (Ex. Canthrellus).

Example of rudimentary gills

Example of rudimentary gills3) Mushrooms with a pore surface: These species have a sponge-like pore surface instead of blade-like gills (Ex. Boletus, Suillus, Chalciporus). Pay attention to pore morphology; are the pores small and round? or are they larger and elongated?

Example of mushroom with pores

Example of mushroom with pores4) Mushrooms with tiny pores and a woody texture: These species are often associated with rotting wood. The underside of the cap has a pore surface like the boletes, however, the pores are tiny and the overall texture of the mushroom is reminiscent of wood (Ex. Fomitopsis, Polyporus, Phaeolus).

Example of a mushroom with woody texture

Example of a mushroom with woody texture5) Toothed fungi: Species whose spore bearing surface consists of small spine-like projections instead of gills (Hydnum, Sarcodon).

Example of a mushroom with a toothed spore-bearing surface

Example of a mushroom with a toothed spore-bearing surface6) Jelly fungi: Mushrooms that resemble amorphous blobs with a gummy bear like texture (Tremella, Heterotextus, Pseudohydnum).

Example of jelly fungus mushroom

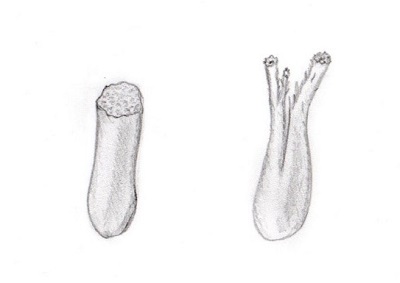

Example of jelly fungus mushroom7) Coral fungi: Mushrooms that resemble marine corals (Ex. Clavaria).

Example of a coral fungus mushroom

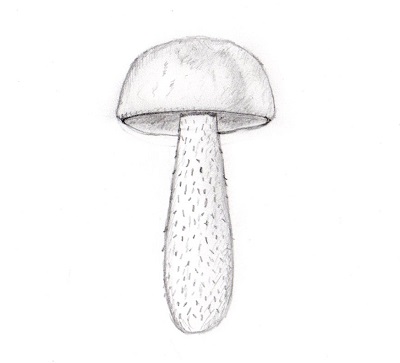

Example of a coral fungus mushroom8) Puffballs: Approximately round fungi with the texture of a marshmallow. The interior of these species (gleba) eventually becomes a mass of spores that are ejected during moments of disturbance through an apical pore that opens at maturity in the top of the mushroom (Ex. Morganella, Clavatia, Geastrum).

Example of a puffball mushroom

Example of a puffball mushroom Another example of a puffball mushroom

Another example of a puffball mushroom9) Mushrooms that appear wrinkled or honey-combed: These mushrooms have a distinct stipe and a cap which often appears honey-combed (Ex. Morchella, Helvella, Verpa).

Example of a wrinkled/honey-combed type of mushroom.

Example of a wrinkled/honey-combed type of mushroom.10) Truffles: Underground fungi that resemble potatoes (Ex. Tuber)

Example of a truffle type of mushroom

Example of a truffle type of mushroom11) Earth tongues: Fungi what resemble narrow flattened tongues (Ex. Trichoglossum).

Example of an earth tongue type of mushroom

Example of an earth tongue type of mushroom12) Bird’s nest fungi: Small fungi found growing on decaying wood that resemble small coffee mugs without a handle which contain small seed-like structures called peridioles that are filled with spores. The peridioles are spread through a process called splash-cup dynamics (Ex. Nidularia).

Example of a bird's next type of mushroom

Example of a bird's next type of mushroom13) Cup fungi: Flattened species with slightly upturned edges giving the fruiting body the appearance of a saucer (Ex. Peziza).

Example of a cup fungus

Example of a cup fungusBe More Prepared For Your Next Outdoor Adventure!

Don't leave home without knowing these six essential survival skills. Our free survival mini guide reveals the strategies of:

- Shelter & fire to prevent the number one cause of death

- Obtaining clean water to avoid life-threatening dehydration

- Common wild survival foods and other critical skills!

Gilled Mushroom Identification:

One of the largest and most important groups of mushrooms to the potential mushroom forager are the gilled mushrooms. The gilled mushrooms pose a challenge to the novice and expert alike due to the huge number of species and the similarities that many species share.

The gilled mushroom group contains many of our most important edible species as well as our most poisonous. Therefore, it is very important to know this group well before attempting to harvest any of its members for food.

Identification Features of the Gilled Mushrooms:

A) Cap Shape - The cap is the most prominent feature of a gilled mushroom, and gives the observer many clues as to the identity of a given species. The cap can vary between species and within species depending upon the age of the individual mushroom.

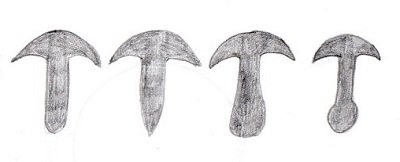

Cap shapes (from left to right): 1) Cylindrical, 2) Conical, 3) Bell-shaped, 4) Umbonate, 5) Convex, 6) Plane,

7) Uplifted, 8) Depressed, 9) Funnel-shaped.

Cap shapes (from left to right): 1) Cylindrical, 2) Conical, 3) Bell-shaped, 4) Umbonate, 5) Convex, 6) Plane,

7) Uplifted, 8) Depressed, 9) Funnel-shaped.Other cap characteristics:

Some smaller features of the cap can also be used during the ID process such as the remnants of the universal veil (see below) (1), the presence or absence of tomentum (dense hair) (2), marginal striations (3), and viscosity (a slimy layer on the cap) (4).

1. remnants of the universal veil on the cap

1. remnants of the universal veil on the cap 2. example of dense hair on the cap

2. example of dense hair on the cap 3. marginal striations on the cap

3. marginal striations on the cap 4. slimy layer on the cap

4. slimy layer on the capThe universal veil is a sac-like structure that covers the entire mushroom during the early stages of development protecting the developing primordia.

The remnants of the veil tissue can also be appendiculate (clinging to the margins of the cap).

remnants of veil tissue clinging to the margins of the cap

remnants of veil tissue clinging to the margins of the capCap coloration:

Cap color is another variable to bear in mind during the identification process. Many species of mushroom have only a single cap color while other species have multiple color morphs.

The best known example of multiple morphs occurs with Amanita muscaria, (the fly algaric). In this species the cap color varies from yellow to red.

Also, bear in mind that cap color can change with age and often lightens if a particular individual becomes overly hydrated.

B) Gill Characteristics (gill attachment):

From left to right:

1) Free- Gills do not attach to the stipe.

2) Adnexed- Gills narrowly attached to the stipe.

3) Adnate- Gills broadly attached to the stipe.

4) Sinuate- Gills notched near the stipe.

5) Decurrent- Gills extending down the stipe.

Gill characteristics (gill spacing):

The spacing of the gills on a mushroom vary from densely packed on some Coprinus species (1) to the greater spacing seen on species in the Genus Hygrophorus and Laccaria where obvious space exists between the gill plates (2).

1. densely-packed gill spacing

1. densely-packed gill spacing 2. greater gill spacing

2. greater gill spacingRemnants of the universal veil tissue:

In the genus Amanita the bottom of the stipe (the portion nearest the ground surface) has a sac-like structure called the volva. The volva can vary in morphology from bulb-like without a distinct lip (1), to specimens with a very distinct lip (2).

1. bulb-like volva without a distinct lip

1. bulb-like volva without a distinct lip 2. volva with distinct lip

2. volva with distinct lipCharacteristics of the Stipe:

Shape:

The shape of the stipe can aid in the identification of mushrooms.

From left to right:

1) Equal- The stipe remains approximately the same width throughout its length.

2) Tapered- The stipe tapers toward the end.

3) Clavate- The overall shape of the stipe resembles a club.

4) Bulbous- The stipe has a distinct rounded end.

Stipe cap attachment:

Another feature to look at is how the stipe attaches to the cap:

1) Central attachment: The stipe attaches to the cap at its center.

2) Lateral attachment: The stipe attaches to the cap in an off-center position.

3) No attachment: The mushroom lacks a stipe.

1. central attachment of the stipe

1. central attachment of the stipe 2. lateral attachment of the stipe

2. lateral attachment of the stipe 3. no stipe

3. no stipeCharacteristics of the partial veil remnants:

The partial veil is a structure that covers the gills of a mushroom until the mushroom is ready to release spores. The partial veil provides protection to the spore producing surface.

The remnants of the partial veil often form a shirt-like ring (annulus) around the stipe of the mushroom. The ring morphology can vary by species. Some species having rings that are lax (1), while others have rings that are more where the ring used to be (the ring zone), which are stereotypically ring-like (2).

Mushrooms in the genus Cortinarius have a distinct partial veil that resembles fine cob webs (3). Some species in the Genera Lepiota, and Chlorophyllum have rings that are double edged (See #2 in the picture sequence below). In some instances the ring will break down leaving a discolored area on the stipe.

1. lax veil remnants

1. lax veil remnants 2. ring-like veil remnants

2. ring-like veil remnants 3. cob-web-like veil remnants

3. cob-web-like veil remnantsOther stipe characteristics:

1) Reticulations (net-like patterns) - Some mushrooms will have reticulations at the apex of the stipe near where the stipe and the cap meet.

net-like patterns where the stipe meets the cap

net-like patterns where the stipe meets the cap2) Scabrous (clumps of fibers) - The stipe is covered with small often dark colored fibrils.

scabrous stipe

scabrous stipe3) Punctate- The stipe will have small dark spots (not fibrils) along the length of the stipe (often seen in the genus Suillus).

punctate stipe (small dark spots)

punctate stipe (small dark spots)Staining Reactions:

Some species of mushroom stain distinctive colors when bruised. For instance, many species in the genus Boletus (1) stain blue when the flesh is compressed. Pay attention to the bruising coloration, as well as how long it takes for the mushroom to stain.

Another reaction to mechanical damage can be seen in the genus Lactarius (2) where the cap will bleed a latex-like substance when injured. Pay close attention to latex coloration, as well as whether or not the latex changes color over time.

1. blue staining

1. blue staining 2. latex-like substance

2. latex-like substanceUsing Your Other Senses for Mushroom Identification:

Visual morphological features are key in the process of mushroom ID. However, don’t ignore other sensory information during the process.

A) Smell and taste:

Many species of mushrooms have distinct odors. Crush a piece of the cap and smell. Relating to the sense of smell is taste. It is safe to taste a small portion of the cap to see if the taste is distinct. The genus Russula is often partly differentiated by how acrid the flavor of the cap is. When sampling the cap of an unknown species make sure to spit out the bite instead of swallowing.

B) Texture and density:

Another detail to pay attention to is texture and density. Some species have a jelly-like texture, some are solid but soft, while others have a dense almost wood-like consistency.

C) Fracture:

The genus Russula has a distinct texture due to the shape of the cells (round) in the mushroom. In Russula the cap and stipe will snap like chalk when pressure is applied. Other species are more fibrous leaving pieces of tissue dangling from the break as opposed to the clean break in a linear plane of the Russula. Still other species will bend significantly without breaking due to the wood-like texture of the flesh.

Left: snapped stipe. Right: fibrous stipe break.

Left: snapped stipe. Right: fibrous stipe break.Conclusion:

Despite the challenges inherent in learning wild mushroom identification, the rewards are well worth the difficulties. Mushrooms provide us with food, medicine, and insights into the world around us!

By the way, when you're out foraging, it's important to know how to stay safe in the outdoors, especially if you were to get lost. Right now you can get a free copy of our mini survival guide here, where you'll discover six key strategies for outdoor emergencies, plus often-overlooked survival tips.

Additional Resources on Mushroom Identification:

The Complete Mushroom Hunter, Revised by Gary Lincoff

Learn foraging skills and more at our Wild Mushroom Identification Class.

Additional Alderleaf Articles on Mushrooms:

Types of Mushrooms: For Medicine and Permaculture

Chantrelle Mushrooms: Gifts of the Forest

About the Author: Chris Byrd is an instructor at Alderleaf. He has been teaching naturalist skills for over twenty years. Learn more about Chris Byrd.

Return from Mushroom Identification back to Wild Foods Articles

Is The Essential Wilderness Survival Skills Course Right for You? Take the "Online Survival Training Readiness" Quiz

See for yourself if this eye-opening course is a good fit for you. It takes just a few minutes! Get your Survival Training Readiness Score Now!

Grow Your Outdoor Skills! Get monthly updates on new wilderness skills, upcoming courses, and special opportunities. Join the free Alderleaf eNews and as a welcome gift you'll get a copy of our Mini Survival Guide.

The Six Keys to Survival: Get a free copy of our survival mini-guide and monthly tips!

The Six Keys to Survival: Get a free copy of our survival mini-guide and monthly tips!

Learn more