Wolverine Tracks and Sign

By Chris Byrd

Wolverine tracks and sign can be challenging to find. This enigmatic and elusive mesocarnivore is found in the western United States and other northern regions around the globe. Rich in history and mythology the wolverine has been sparking the imaginations of native peoples and outdoor enthusiasts for centuries!

Description

The wolverine is a medium sized animal (14-44 lbs.) with males being slightly larger than females.

Wolverines are dark brown with two yellowish stripes running down the sides of the body from the shoulders to the base of the tail. Some animals possess lighter areas on the chest, which can be used to distinguish individual animals.

Their heads are large with thick necks and the rostrum is dark with a yellow forehead and yellow along the top of the ears.

The tail is short and bushy and the limbs are short with large feet in proportion to the thick, rather bear-like body.

Their fur consists of guard hairs that are long, coarse, and hydrophobic, with side and dorsal guard hairs measuring 10 cm, and rump and tail hairs measuring 20 cm. Underneath the guard hair is a dense layer of coarse, wooly underfur 2-3 cm in length.

Wolverines also possess scent glands on either side of the anus, as well as sebaceous glands on the abdomen.

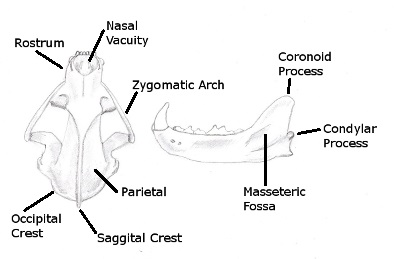

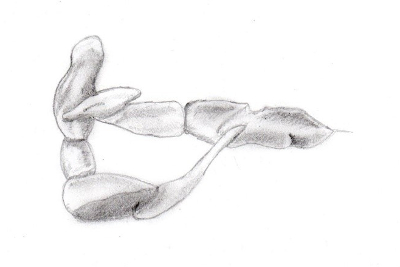

Skull Morphology

Wolverines have dense, heavy skulls that are wedge-shaped. The rostrum is short, and the dorsal portion of the skull has prominent sagittal, and occipital crests. The sagittal crest often overhangs the posterior portion of the skull, especially in older males.

Wolverines have a barrel shaped condylar process on the mandible that fits tightly into the temporal mandibular joint. Even after death the mandible can be difficult to remove from the skull.

Wolverines show a number of skull adaptations that provide advantages for their carnivorous/scavenger lifestyle. The skull has an enlarged sagittal crest, pitting on the parietal bones, and wide spreading zygomatic arches.

Combined with their curved mandible, and the fact that the condylar process is in line with the tooth rows, the wolverine has excellent power in the anterior portion of the skull with large temporalis muscles for biting with their canines.

Wolverines also have relatively hefty zygomatic arches and a well-developed masseteric fossa on the mandible, which give strength to the masseter muscles that control the molars.

The tight articulation between the condylar process and the temporomandibular joint means that wolverine have little lateral jaw movement while chewing, however the lack of side-to-side movement gives them extra crushing power to break open bones in search of marrow.

Habitat and Distribution in Washington State

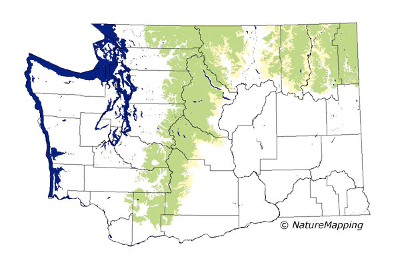

Wolverines tracks are found in circumboreal areas of the world. In the Continental United States, wolverines are found in the Rocky and Cascade mountain ranges of the west.

Wolverines inhabit both forested and open habitats such as alpine tundra and subalpine parkland. In Washington, wolverines primarily use high elevation mixed montane and mixed subalpine conifer forest from elevations of 4,431 to 5,910 ft. A smaller portion of their time is spent in areas of higher or lower elevations.

Wolverines tend to use higher elevations in the summer and lower elevation in the winter. Most wolverine activity in Washington occurs east of the Cascade crest with the majority occurring in the eastern portion of the North Cascades.

The furthest west a reliable sighting occurred was on Sauk Mountain from a radio collared wolverine known as Special ‘K’.

Most Wolverines in Washington are found north of Stevens Pass, although two sightings have occurred south of Stevens near Mount Rainier and Mount Adams in the South Cascades. Another detection has occurred in the Kettle Range of Eastern Washington.

GAP analysis of predicted distribution of wolverines in Washington State. Green areas represent core breeding habitat, yellow represent marginal breeding habitat. Obtained from the Washington Gap Analysis Mammal Volume by Dave Lester.

GAP analysis of predicted distribution of wolverines in Washington State. Green areas represent core breeding habitat, yellow represent marginal breeding habitat. Obtained from the Washington Gap Analysis Mammal Volume by Dave Lester.History in Washington State

Wolverines were extirpated in Washington in the early 1900’s due to overharvesting for the fur trade. In the 1990’s wolverines were detected in the Cascade Mountain Range. The animals that have recolonized the Cascades are genetically related to animals in the Coast range of British Columbia.

Social System

Wolverines are typically solitary except for females with young. Recent studies however are beginning to point towards more complicated intraspecific social relationships. Male wolverines have been documented interacting positively with their offspring, including male offspring, from previous years into the sub-adult life stage.

Reproduction

Wolverines are polygamous with one male doing most of the breeding over a large area during the April-August breeding season. Females dig natal dens underneath logs and rock piles in rugged subalpine and alpine areas away from human infrastructure. Dens consist of a tunnel system with typically 2 kits born in a chamber at ground level. Den sites have at least 1 meter of snow cover throughout the spring and likely provides thermoregulatory and predator defenses.

Development

Wolverine kits are typically born Jan-April. Kits first leave their natal den after the first period of warmer weather (several days of above freezing temperatures).

The kits are then typically moved to a maternal den site. The kits are weaned at 7-8 weeks and typically disperse at 13 months, although the kits may remain in the mother’s territory for up to 2 years.

Be More Prepared For Your Next Outdoor Adventure!

Don't leave without knowing these six essential survival skills. Our free survival mini guide reveals the strategies of:

- Shelter & fire to prevent the number one cause of death

- Obtaining clean water to avoid life-threatening dehydration

- Common wild survival foods and other critical skills!

Movement and Home Range

Wolverines have very large home ranges that they typically cover over a period of several weeks often in figure 8 patterns. Male wolverines have home ranges in Washington that can approach as much as 3,000 square kilometers during the breeding season. Females have smaller home ranges, and females with young kits have the smallest home range of all.

Wolverine home ranges typically overlap the ranges of other wolverines. Males have home ranges that overlap the ranges of multiple females, however males are usually intolerant of other unrelated males within their territories. Females also typically exclude other females from their home ranges.

Feeding

Wolverines are carnivores that both hunt and scavenge. Wolverine have an excellent sense of smell that helps them locate carcasses; and their aggressiveness towards other predators enables them to push other carnivores off carcasses and kills.

Wolverines, despite their masterful ability to scavenge, are also very capable hunters.

Ungulates are hunted in late winter when freeze/thaw cycles make it difficult for them to stay on the snow surface. Wolverines are capable climbers and diggers allowing them access to a wide variety of smaller prey animals.

Wolverines also form food caches that allow them access to food during times of scarcity. They mark their caches with secretions from their anal glands, which may deter scavengers.

Predation and Competition

In one study in the North Cascades of Washington, multiple radio collared animals died as the result of interaction with other carnivores, likely cougars. Gray wolves will also occasionally kill wolverines. Intraspecific mortality is also known. Males will kill the offspring of other males, and the dominant animal within a home range may kill dispersing individuals.

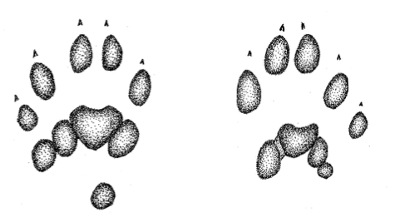

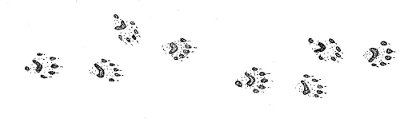

Wolverine Tracks

Wolverines have large plantigrade feet with five toes on each foot. The claws are moderate in size, and may or may not register in tracks.

The metacarpal and metatarsal pads show strong lobation of the fused pads (the pad appears to be a fusing of a series of smaller pads).

The front foot also has a rounded carpal pad that registers posterior of the metacarpal pad and sits along the outside edge of the track. Front tracks are slightly larger than hind tracks, but appear similar in size.

The feet are heavily furred, especially in winter, causing the track to appear diffuse and blurry.

On both the front and hind wolverine tracks, toe 1 is smallest and lowest with toe 1 on the hind track being lower than toe 1 on the front track giving the hind track a more asymmetrical appearance. When toe 1 does not register the hind foot looks similar to track of a canine.

Front right and left hind

Front right and left hindWolverine tracks measurements:

Front track: 3 ½- 6 in. (L) x 3 ½-5 in. (W)

Hind track: 3 1/2 -6 in. (L) x 3 1/4 -5 ¼ (W)

Gaits and Wolverine Tracks Patterns

Wolverines typically move throughout their home range in various loping gaits (often a 4 by 4, or 3 by 4, or 2 by 2 lope). Wolverine will also walk when investigating potential food sources, or to scent mark.

wolverine tracks walking gait pattern

wolverine tracks walking gait pattern wolverine tracks 4 x 4 loping gait pattern

wolverine tracks 4 x 4 loping gait pattern wolverine tracks 2 x 2 loping gait pattern

wolverine tracks 2 x 2 loping gait patternSign

Wolverine scats, like other members of the Mustelidae, are long, twisted and tapered ropes, filled with bone and fur.

The ends of the scats are usually tapered. Longer scats may be doubled back over themselves. Wolverines like other Mustelids will leave scats on elevated surfaces within their territories.

Wolverine mark their home ranges by scratching trees and beating up saplings and other vegetation, as well as by urinating and possibly rubbing the glands along the abdomen over objects. Wolverine will roll and over mark the trails of other animals.

Bone fragments may be found in areas where wolverines have fed.

wolverine scat

wolverine scatDespite the wealth of new information currently emerging on the life history of the wolverine, it remains a creature of relative mystery. Finding wolverine tracks can often feel like searching for a needle in a haystack. Global climate change may greatly affect the wolverine, especially here in Washington at the southernmost extension of its range.

By the way, when you're out tracking or looking for wild animals, it's important to know how to stay safe in the outdoors, especially if you were to get lost. Right now you can get a free copy of our mini survival guide here, where you'll discover six key strategies for outdoor emergencies, plus often-overlooked survival tips.

References

Aubry, K. B. (2016). Wolverine Distribution and Ecology in the North Cascades Ecosystem Final Progress Report. US Forest Service. 2012-2016.p.

Elbroch, M. (2003). Mammal Tracks and Sign: A Guide to North American Species. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

Elbroch, M. (2006). Animal Skulls: A Guide to North American Species. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

Elbroch, M., et al. (2012). Field Guide to Animal Tracks and Scat of California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Feldhamer, G. A., et al. (2003). Wild Mammals of North America. Biology Management and Conservation. (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kays, R. W., and Wilson, D. E. (2009). Mammals of North America. (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Murie, O. J., et al. (2005). Peterson Field Guide: Animal Tracks. (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Reid, F. A. (2006). Mammals of North America. (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Additional Resources on Wolverine Tracks:

Wolverine Tracks Information from the Wolverine Foundation

Learn how track animals - check out our Wildlife Tracking Courses.

About the Author: Chris Byrd is an instructor at Alderleaf. He has been teaching naturalist skills for over twenty years. Learn more about Chris Byrd.

Return from Wolverine Tracks & Sign back to Wildlife Tracking Articles

Is The Essential Wilderness Survival Skills Course Right for You? Take the "Online Survival Training Readiness" Quiz

See for yourself if this eye-opening course is a good fit for you. It takes just a few minutes! Get your Survival Training Readiness Score Now!

Grow Your Outdoor Skills! Get monthly updates on new wilderness skills, upcoming courses, and special opportunities. Join the free Alderleaf eNews and as a welcome gift you'll get a copy of our Mini Survival Guide.

The Six Keys to Survival: Get a free copy of our survival mini-guide and monthly tips!

The Six Keys to Survival: Get a free copy of our survival mini-guide and monthly tips!

Learn more